A noted film historian saw Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! for the first

time a few years ago. Intrigued by the 1933 minor classic's charms

and Al Jolson's atypicai performance in it, he sought as much information

about the film as was available. But his efforts were to no

avail. Despite his desire and a number of well-placed sources he

consistently came up against a blank brick wall regarding the movie's

pre-production and shooting history. He concluded that it was almost

as if someone wanted the film shrouded in rumor, legend and

outright lies forever.

A noted film historian saw Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! for the first

time a few years ago. Intrigued by the 1933 minor classic's charms

and Al Jolson's atypicai performance in it, he sought as much information

about the film as was available. But his efforts were to no

avail. Despite his desire and a number of well-placed sources he

consistently came up against a blank brick wall regarding the movie's

pre-production and shooting history. He concluded that it was almost

as if someone wanted the film shrouded in rumor, legend and

outright lies forever.

Whatever the veracity of that historian's conclusion, any contemporary Jolson researcher finds himself up against the same brick wall when he attempts to gather facts about Jolie's sixth feature film. If one discounts the usual public relations articles that appeared in 1933 movie magazines, the fact remains that there is almost no reliable information available today about the film that was probably Al Jolson's best cinematic effort. This article will attempt to provide as much materiai about it as is possible fifty years after its premiere.

INTRODUCTION

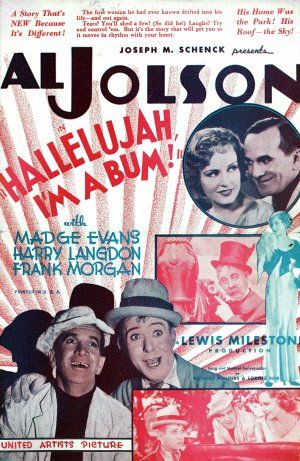

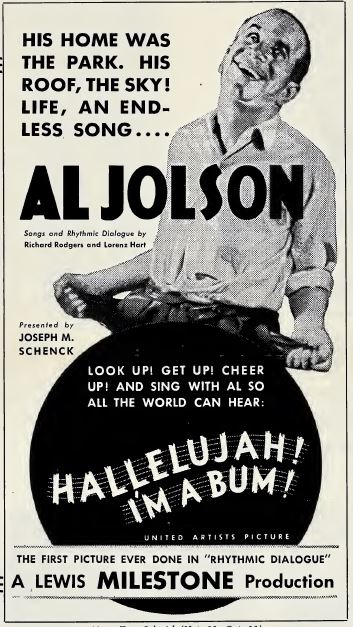

Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! remains today a minor classic of 1930's cinema, regarded by many film buffs as falling just a hair short of "great". The movie was the result of a daring experiment by an inspired team of unique Hollywood taients.

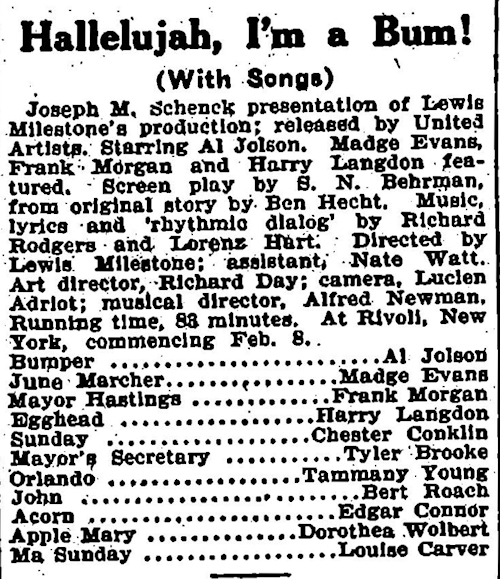

On paper, it looked like a winner: a score by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart; a story by noted author Ben Hecht; directed by the brilliant Lewis Milestone; a 40-piece symphony orchestra led by Alfred Newman; and starring the world's greatest entertainer, Al Jolson. The film was intended to combine Hollywood musicai escapism with a bitter dose of Depression-era reaiity. (It remains today one of the only American films of the early Depression that faced the hard times head on.) The film succeeded in this … perhaps, too well for its own good.

Producer Joseph Schenck bet heavily that the ticket-buying public

was ready for "rhythmic dialogue" — an ingenious technique of rhymed

couplets, sung/spoken to the accompaniment of Newman's orchestra.

In this way, the lyrics and music were an integral part of the story

instead of being just "songs" as such.

Producer Joseph Schenck bet heavily that the ticket-buying public

was ready for "rhythmic dialogue" — an ingenious technique of rhymed

couplets, sung/spoken to the accompaniment of Newman's orchestra.

In this way, the lyrics and music were an integral part of the story

instead of being just "songs" as such.

Unfortunately, the sophistication of the technique plus the audience's unwillingness to suspend disbelief became an obstacle too difficult for "rhythmic dialogue" to overcome. The film was regarded by many as something of an oddity, and it often played to nearly empty movie theaters. Panned critically, the film, the studio and the star took quite a beating.

Viewed half a century later, Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! is surprisingly modern. It is a prime example of a film that was truly ahead of its own time. Many cinema students in American college courses considered it a "must see" film for the 1980s, and it is frequently shown at the college film circuit where it has picked up a remarkable following. (In some instances, it has developed its own "cult" with some college kids reportedly having seen the movie more than twenty times!)

Certainly then, there was something very right about Hallelujah, I'm A Bum!. Unfortunately, something was very wrong with it, too. The film was an expensive failure for United Artists, costing about $1.25 million. But the failure of the film was even more costly to Al Jolson's career, for the difficulties before and during shooting put Jolie out of circulation in Hollywood for two years. The talking screen was the new master of show business and Al Jolson's time consuming hiatus severely hurt a career that just a few years before had been considered absolutely indestructible.

PRODUCTION HISTORY

Joseph Schenck, head of United Artists, was a dear friend of Al Jolson — maybe one of his oldest. Both men had met each other years before back East, when Joe had headed the Loew Organization with his brother.

In December, 1928, Al and wife, Ruby Keeler, were on vacation in Paim Springs. Al's triumph in The Singing Fool was well-known by everyone in the English-speaking world, and Sonny Boy was being crooned by every singer in the land.

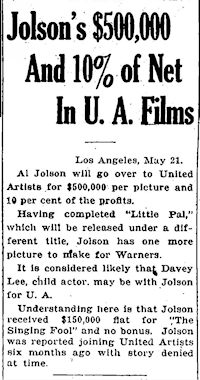

Al visited his old friend Joe, and the two men found themselves

sunbathing on the roof. What ensued has become a Hollywood

legend — but, for a change, this one is true. Joe asked Al for a favor.

A big one. Would Jolie agree to help his pai by starring in a number

of United Artists features as soon as his current contract with the

Warners expired? Schenck offered Al a deai — a four-film package at

$25,000.00 per week for 40 weeks. Jolson accepted, and since there

was no writing paper handy (let alone a lawyer!), the contract was

hand-written on a brown paper bag that had contained a snack for

the two sunbathers — bananas. (This famous agreement is referred

to even today as "the banana bag contract".)

Al visited his old friend Joe, and the two men found themselves

sunbathing on the roof. What ensued has become a Hollywood

legend — but, for a change, this one is true. Joe asked Al for a favor.

A big one. Would Jolie agree to help his pai by starring in a number

of United Artists features as soon as his current contract with the

Warners expired? Schenck offered Al a deai — a four-film package at

$25,000.00 per week for 40 weeks. Jolson accepted, and since there

was no writing paper handy (let alone a lawyer!), the contract was

hand-written on a brown paper bag that had contained a snack for

the two sunbathers — bananas. (This famous agreement is referred

to even today as "the banana bag contract".)

Only a month before, Al had signed a three-picture deal with Warners, so he insisted to Joe that nobody know of their agreement as yet. Schenck agreed, and for a year nobody did.

|

Click to read 1930 article about

Sons O' Guns |

Jolie, now with no UA project at hand, headed East and wound up back on the Broadway stage in The Wonder Bar.

By January, 1932, Schenck considered Sons O' Guns to be aiready outdated and began to search for something new. It was at about this time that Ben Hecht showed Joe a short story that he cailed The Optimist which Joe liked immediately. Reinforced by Lewis Milestone, head of production at UA, he headed to Chicago to visit Jolson in his hotel room. Schenck was convinced that he'd found his Jolson property at last!

Jolson was intrigued and headed out to the coast full of steam and raring to go. Unfortunately, the studio was woefully unready for him. Two months later he found himself sitting in his speciai cottage on the UA lot just waiting for the front office to get started. It would be a long, difficult wait. UA was having major problems whipping The Optimist into shape. Jolson sat and fumed. In May he booked himself for two more weeks of personai appearances. Finaily in June, Al saw the initial shooting script … and hated it. He called his friend Irving Caesar to the coast for some emergency repair work but Caesar, too, felt that it was ail wrong. By this time, however, the studio cameras were at last set to roll so Al, apprehensive and worried now about the entire project, started filming in July.

The first day on the set was a total disaster. Director, Harry D'Arrast

clashed immediately with the star and quit. Schenck replaced him

with Chester Erskine who attempted to calm the waters with some

new ideas. Eventually, however, Schenck, disturbed by the knowledge

that the film was not going well, turned to Lewis Milestone

once again.

The first day on the set was a total disaster. Director, Harry D'Arrast

clashed immediately with the star and quit. Schenck replaced him

with Chester Erskine who attempted to calm the waters with some

new ideas. Eventually, however, Schenck, disturbed by the knowledge

that the film was not going well, turned to Lewis Milestone

once again.

And so in September, 1932, two months after the cameras started to

roll, UA decided to scrap most of what they had in the can! They

would start anew, this time with Milestone firmly in control. It was

at this time that Roland Young, the actor who had been playing

Mayor Hastings, was forced to leave the film for reasons given as in ill

heaith. He was replaced by Frank Morgan (later of Wizard of Oz fame).

And so in September, 1932, two months after the cameras started to

roll, UA decided to scrap most of what they had in the can! They

would start anew, this time with Milestone firmly in control. It was

at this time that Roland Young, the actor who had been playing

Mayor Hastings, was forced to leave the film for reasons given as in ill

heaith. He was replaced by Frank Morgan (later of Wizard of Oz fame).

Milestone virtuaily remade the movie from late September through early November. Jolson's last scene was shot November 14, aithough he did have to return for some retakes. Jolson was totally finished by December 2, at which time he headed East more than grateful to be finished at last with the entire project.

THE STORY

Opening in the Everglades of Florida, the film finds Bumper (Jolson),

Mayor of the hobos in Central Park, on vacation with his buddy

Acorn (Edgar Connor). They encounter the real Mayor of New

York, John Hastings (Frank Morgan), who is on a duck hunting

escape from the burdens of his office. The two Mayors are old

friends. along with Acorn they sit down to dine on the duck illegally

shot by the Mayor.

Opening in the Everglades of Florida, the film finds Bumper (Jolson),

Mayor of the hobos in Central Park, on vacation with his buddy

Acorn (Edgar Connor). They encounter the real Mayor of New

York, John Hastings (Frank Morgan), who is on a duck hunting

escape from the burdens of his office. The two Mayors are old

friends. along with Acorn they sit down to dine on the duck illegally

shot by the Mayor.

The three return to New York — the Mayor via his private railroad car

and Bumper and Acorn via foot, rail and wagon. Within the comfort

of his car the Mayor broods over his accusation that June Marcher

(Madge Evans), his girlfriend, is still interested in, and has given

money to, her ex-boyfriend.

The three return to New York — the Mayor via his private railroad car

and Bumper and Acorn via foot, rail and wagon. Within the comfort

of his car the Mayor broods over his accusation that June Marcher

(Madge Evans), his girlfriend, is still interested in, and has given

money to, her ex-boyfriend.

Back in Central Park, Bumper croons and whistles his peculiar call alerting his constituents who assemble to welcome him back. Among his friends is Egghead (Harry Langdon), the park custodian, who dislikes the tramps but dislikes the rich and the Establishment even more. Sunday (Chester Conklin) is aiso there to drive Bumper to his daily encounters with Mayor Hastings. Bumper aiways greets the Mayor as he leaves his taxi at noon time for his daily lunch at the Casino in Central Park. Acting as doorman, Bumper is rewarded each time with a dollar tip.

The day that he returns to New York, Mayor Hastings reconciles with June at the Casino and gives her a $1000 bill. Inadvertently, she leaves her purse behind when the Mayor escorts her home.

Later that evening when the Mayor is to meet June for a date, she tells him about the lost purse with the money in it. The Mayor refuses to believe her, thinking that she is still helping her old boyfriend. June decides to leave the Mayor and disappears.

The next day, Bumper finds the purse with the money. Inside is a

postcard addressed to Miss June Marcher from her ex-boyfriend

which proves conclusively that June is innocent of the mayor's

charges. The tramps insist that Bumper keep the money but he will

have none of that. He tries to return it to its rightful owner, but

discovers that she has already gone and accidentally meets Mayor

Hastings in the owner's apartment. In a clarifying discussion between

the two men, the Mayor explains that June Marcher is his

girlfriend and he now reaiizes that she is innocent. He immediately

sounds a police alarm to locate her.

The next day, Bumper finds the purse with the money. Inside is a

postcard addressed to Miss June Marcher from her ex-boyfriend

which proves conclusively that June is innocent of the mayor's

charges. The tramps insist that Bumper keep the money but he will

have none of that. He tries to return it to its rightful owner, but

discovers that she has already gone and accidentally meets Mayor

Hastings in the owner's apartment. In a clarifying discussion between

the two men, the Mayor explains that June Marcher is his

girlfriend and he now reaiizes that she is innocent. He immediately

sounds a police alarm to locate her.

The Mayor insists that Bumper keep the $1000. Later that night Bumper returns to the park to distribute the money to his followers who are jubilant. While they are enjoying the money, Bumper saves a strange girl from suicide in the park lake. Unknown to him, she is the Mayor's missing girlfriend, June.

He discovers that she has amnesia and names her Angel. He persuades

Sunday to rent her a room in his house much to Ma Sunday's

(Louise Carver) jealous annoyance. Angel has caused Bumper to

take an interest in a job, so deserting his hobo friends, he and Acorn

accept jobs in a bank, arranged for by Mayor Hastings. Bumper is

then tried by a tramp "court" for desertion, but the judge declares

that he has no jurisdiction over Bumper because he is insane. At

the end of the first week Bumper is elated with his pay. So is Acorn,

whose only complaint is that they wasted so much time making it!

He discovers that she has amnesia and names her Angel. He persuades

Sunday to rent her a room in his house much to Ma Sunday's

(Louise Carver) jealous annoyance. Angel has caused Bumper to

take an interest in a job, so deserting his hobo friends, he and Acorn

accept jobs in a bank, arranged for by Mayor Hastings. Bumper is

then tried by a tramp "court" for desertion, but the judge declares

that he has no jurisdiction over Bumper because he is insane. At

the end of the first week Bumper is elated with his pay. So is Acorn,

whose only complaint is that they wasted so much time making it!

That night Bumper eagerly returns to Angel's room with gifts he has

bought her. Angel tells him how much she needs him, and while

they are dancing to the music which wafts across the street from the

dance hail, they are interrupted by Sunday who tells Bumper that

his friend the Mayor is drunk downstairs in a taxi. Bumper goes to

his aid as he tells Angel he will be back shortly. Back at his apartment,

Mayor Hastings shows Bumper a picture of his girl June, and

Bumper sadly reaiizes it is his own Angel. Unselfishly, he returns

the Mayor to Angel's room and, as the Mayor goes through the

front entrance, Bumper tries to disappear but Angel spots him from

the fire escape and asks where he is going. She tells Bumper how

much she needs him. Suddenly, there is a knock at the door, and as

June opens the door for the Mayor, she regains her memory. Disheartened,

Bumper returns to his old life and pals in the park. A

vagabond's quest for love and convention ends in bittersweet resignation

that life on the road, and not romance, is his destiny.

That night Bumper eagerly returns to Angel's room with gifts he has

bought her. Angel tells him how much she needs him, and while

they are dancing to the music which wafts across the street from the

dance hail, they are interrupted by Sunday who tells Bumper that

his friend the Mayor is drunk downstairs in a taxi. Bumper goes to

his aid as he tells Angel he will be back shortly. Back at his apartment,

Mayor Hastings shows Bumper a picture of his girl June, and

Bumper sadly reaiizes it is his own Angel. Unselfishly, he returns

the Mayor to Angel's room and, as the Mayor goes through the

front entrance, Bumper tries to disappear but Angel spots him from

the fire escape and asks where he is going. She tells Bumper how

much she needs him. Suddenly, there is a knock at the door, and as

June opens the door for the Mayor, she regains her memory. Disheartened,

Bumper returns to his old life and pals in the park. A

vagabond's quest for love and convention ends in bittersweet resignation

that life on the road, and not romance, is his destiny.

POST PRODUCTION

The film opened in New York on February 8, 1933, to generaily awful reviews. (The sole major exception was the New York Times.) The audiences stayed away in droves. At a time in his career when Jolson desperately needed a movie triumph, the criticai and box office faiure of Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! could not have come at a worse time. And while it is too simplistic to blame ai's career slump of the 1930's solely on the failure of the movie, there is a strong element of truth in this commonly held belief, for during the long months of foot-dragging and behind-the-scenes fighting, ai Jolson was out of the eye of Hollywood producers. Since he still had quite a distance to go on the "banana bag contract" — three more films for UA — Jolson was "hands off'. It proved to be a painfully expensive situation for the star. The man who had fired the world's imagination in The Jazz Singer was now left behind in the dust. The great momentum achieved by his first two movies would never again be reaiized.

"Rhythmic dialogue" died a quick death. Hallelujah, I'm A Bum!

finished it off. Rogers and Hart had used the idea successfully

in Love Me Tonight and The Phantom President but the

negative reviews for the Jolson film proved too powerful to combat.

The movie surfaced in The United Kingdom as Hallelujah! I'm A Tramp.

United Artists recognized that the word "bum" was an

anatomicai reference in England, so Jolie had been forced to rerecord

certain songs and scenes for British distribution only. Prints

of both Bum and Tramp exist today, enabling us to hear Bumper

advising Egghead to "screw, bum, screw" in America, and to "blow,

mug, blow" in England!

"Rhythmic dialogue" died a quick death. Hallelujah, I'm A Bum!

finished it off. Rogers and Hart had used the idea successfully

in Love Me Tonight and The Phantom President but the

negative reviews for the Jolson film proved too powerful to combat.

The movie surfaced in The United Kingdom as Hallelujah! I'm A Tramp.

United Artists recognized that the word "bum" was an

anatomicai reference in England, so Jolie had been forced to rerecord

certain songs and scenes for British distribution only. Prints

of both Bum and Tramp exist today, enabling us to hear Bumper

advising Egghead to "screw, bum, screw" in America, and to "blow,

mug, blow" in England!

In 1937, Atlantic Pictures obtained rights to the film and, after some

editing, reissued it as The Heart of New York. It bombed.

In 1937, Atlantic Pictures obtained rights to the film and, after some

editing, reissued it as The Heart of New York. It bombed.

Ten years later, after Al's great comeback in The Jolson Story, The Heart of New York was again reissued with the same familiar results.

In the summer of 1973, a gentleman named Barnard Sackett resurrected Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! after obtaining an originai print from the private vault of Mary Pickford. Using state-of-the-art technology, Sackett re-recorded the soundtrack and integrated some scenes that he thought had been lost for forty years. The result was a positive one — a "new" film found an audience.

When viewed today, Hallelujah, I'm A Bum! almost aiways evokes a favorable response. Those who have not seen Jolson before are usuaily stunned by his performance. Expecting a black-faced cartoon character bellowing "Maaammmyyy!", they are instead confronted with a charming, urbane Jolson whose "Bumper" is more like the reai Al Jolson than many people realize.

The movie has been seen on many Public Broadcasting Stations in America, and has aiso been seen on cable TV. It seems that the film is finally being appreciated and enjoyed … sadly, haif a century too late.